UNGA 80 and The Sahel Dilemma

Ryan Parada • September 17, 2025

When world leaders take the podium at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) later this month, the Sahel will be one of those problems that keeps resurfacing, messier, deadlier, and more geopolitically tangled each year. For France, which has just wrapped up decades of permanent bases across West Africa, and for Russia, which has stepped into the vacuum with it’s state-directed “Africa Corps,” the 80th session of the United Nations General Assembly is less about speeches and more about positioning: humanitarian relief, regional diplomacy, and the rules of engagement for an era of proxy influence in Africa.

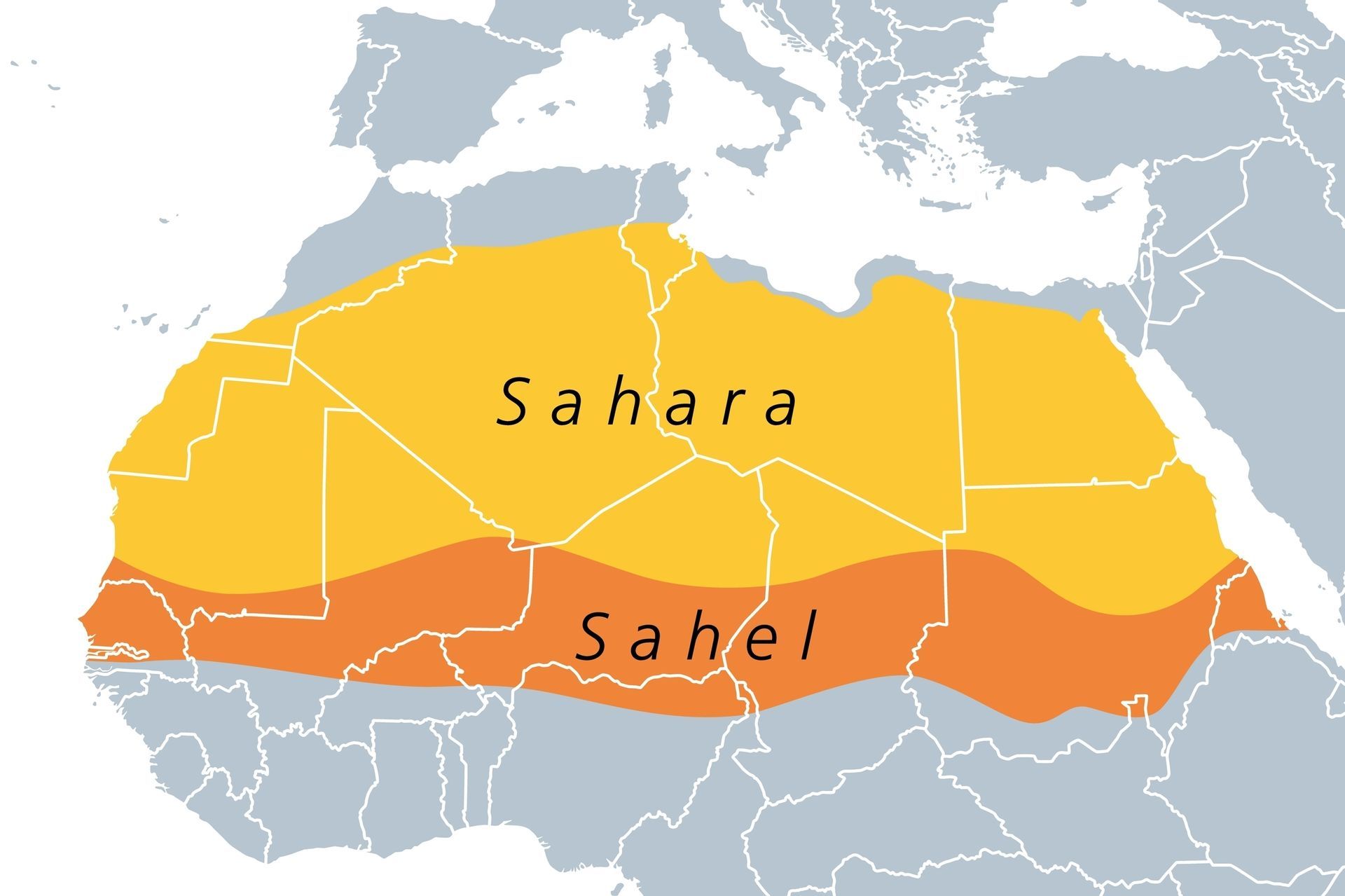

For those less geographically minded, The Sahel is a vast, dry grassland belt that stretches clear across the middle of Africa, running from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. Think of it as the long, semi-arid “transition zone” between the lush, tropical savannas of sub-Saharan Africa to the south and the sands of the Sahara Desert to the north. It cuts through countries such as Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Sudan, and has long been a crossroads of cultures, trade routes, and, today, conflicts.

For those of you who are less then historically minded, France’s presence in the Sahel is rooted in its colonial legacy and a post-independence network of defense agreements across West Africa. After the former French colonies: Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso and others; gained independence in the 1960s, Paris maintained close military and political ties, seeing the region as strategically important for trade, resources, and counterbalancing rivals. In the 2010s, the Sahel became a hotspot for jihadist insurgencies spilling over from Libya’s 2011 collapse and the rise of al-Qaeda- and ISIS-linked groups. France launched Operation Serval in Mali in 2013 to push back militants threatening the Malian capital, later expanding the mission into the broader Operation Barkhane across five Sahel states. Today, even as Paris scales down its footprint amid growing local resentment and competition from Russian mercenaries like the Wagner Group, French forces remain involved, officially to support regional armies and prevent the Sahel from becoming a safe haven for transnational terrorism, but also to preserve long-standing influence in a region once central to its empire.

The Conflict Map: Who’s Fighting Whom, and Where

Three overlapping conflicts define today’s Sahel.

First, the long insurgency led by al-Qaeda-linked Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State’s Sahel affiliate continues to expand and adapt. This year, JNIM has moved from raiding outposts to blockading economies, torching fuel trucks, and threatening supply lines in southern Mali; signaling a strategy to choke states already under stress. Information from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Projct and recent field reporting show the violence cresting not just in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, but spilling toward coastal states and the Benin-Niger-Nigeria borderlands.

Second, the humanitarian emergency is staggering. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) counts nearly 29 million Sahelians in need this year; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) tracks displacement measured in the millions, with Burkina Faso alone hosting over two million internally displaced people. The World Food Programme warns of severe hunger across West and Central Africa during the current lean season, driven by conflict, climate shocks, and price spikes. These are not background numbers; they are the fuel for further instability and forced migration.

Third, the political crisis: the “coup belt.” Since 2020, juntas have taken power in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, then formally quit the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and formed the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), a confederation with mutual defense ambitions and a deliberate pivot away from Western partners. ECOWAS, for its part, has tried a mix of pressure and engagement, lifting many sanctions on Niger last year for humanitarian reasons while urging a path back to civilian rule, but the divorce became official in January 2025.

France’s Retreat and What “After France” Looks Like

France’s decade-long counterterrorism mission (Serval/Barkhane) ended in stages: out of Mali (2022), Burkina Faso (2023), and Niger (2023). By early 2025, even long-standing partnerships in Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal were winding down; in July, Paris formally ended its permanent troop presence in Senegal, effectively closing the chapter on a continuous West African footprint reaching back generations. What remains on the continent is slim: a significant base in Djibouti, and a much-reduced cooperation presence in Gabon. Politically, Paris says it will “reset” relationships around training, intelligence, and crisis response, lighter, less visible, and far more dependent on host-nation consent.

The problem for France is that the security environment worsened as its forces withdrew. Militant fatalities across Africa dipped from the record highs of 2023, but the Sahel remains the deadliest theater on the continent, and JNIM/Islamic State (IS) operations have proven resilient. Even more telling, insurgents now pressure logistics and governance directly (think: fuel blockades), forcing juntas to find external partners who will supply hardware and advisors without governance strings attached.

Russia’s Move: From Wagner to the “Africa Corps” and AES Ties

Moscow has rebranded Wagner’s African networks as the state-run “Africa Corps,” and deepened ties precisely where France and others left off. In April, Russia pledged military support to the AES juntas’ plan for a 5,000-strong joint force. In August, the Russian defense minister hosted the top brass from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger in Moscow, announcing a new cooperation memorandum, equipment, training, and more advisors. The message is simple: Russia will be the security guarantor of last resort where Western conditions are unwelcome. Whether this improves security is another matter, research suggests these deployments prop up regimes but don’t resolve insurgencies.

For AES leaders, this alignment is strategic and political: it buys regime protection, tactical capabilities, and leverage against ECOWAS and Western donors. For Moscow, it is influence on the Atlantic flank, access to resources, and a global stage talking point heading into UNGA: Russia as security partner to the “sovereigntists” of the Sahel.

Could France and Russia Drift Into Open Conflict in Africa?

Short answer: unlikely, but the risk isn’t zero.

- Why unlikely: France has drawn down to avoid exactly that trap. Its posture now centers on Djibouti (far from the Sahel front), bilateral training, and intelligence-sharing with cooperative governments. Paris is also channeling more of its Sahel policy through multilateral fora (EU, UN, AU, ECOWAS) and humanitarian support rather than combat deployments, lowering the odds of uniform-on-uniform run-ins.

- Where friction could happen: Airspace deconfliction, arms deliveries, and contractor-run operations. Russia’s Africa Corps advisors and French security cooperation missions could end up supporting rival political camps in the same crisis (for example, AES versus ECOWAS-aligned neighbors). That creates room for miscalculation, detentions at checkpoints, close air encounters, or “accidental” strikes blamed on the other side. Thus far, however, the French strategy of exiting contested Sahel theaters and the Russian focus on AES strongholds keep the two powers at arms’ length. Expect information warfare to be the more common battleground: influence operations, disinformation, and media narratives.

What UNGA 80 Can Actually Change

UNGA is not going to reverse the coups. It can, however, move three needles if key actors coordinate.

- Humanitarian Surge Tied to Access Guarantees — Agencies are asking for billions to stabilize the Sahel this year. If UNGA can broker practical access, aid corridors, deconfliction for convoys, and guarantees from AES authorities not to harass aid workers, donors can scale faster. A political signal from both AES capitals and coastal states would help keep cross-border operations open as violence spreads southward.

- A UN-Backed Political Lane for ECOWAS–AES Talks — The ECOWAS hard-line sanctions approach has given way to a more pragmatic track. The United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS) briefings have been clear about the dual imperative, counter-terrorism and governance. UNGA side meetings that bring Nigeria (ECOWAS chair), AES foreign ministers, and key partners into a structured dialogue on election timelines, amnesty deals, and joint border security would be time well spent. Even if recognition politics remain frozen, technical cooperation on trade, migration, and counter-smuggling could resume.

- Rules of the Road for Foreign Security Partners — With the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) gone and regional coalitions fluid, UNGA can’t dictate who trains whom, but it can elevate minimum standards: human-rights vetting, transparent basing/contract terms, and reporting on civilian harm. If Russia wants legitimacy for its Africa Corps presence and France wants a credible “lighter-footprint” reset, both should be pressed to accept oversight benchmarks attached to any UN-blessed aid or security assistance packages.

France’s UNGA Play and What to Watch

Paris will lean into three themes in New York:

- Humanitarian Leadership Without Boots on the Ground — Expect French calls to fully fund Sahel appeals and protect aid operations, using the food-security numbers as a rallying cry. This positions France as a partner on relief and resilience while sidestepping the baggage of counterinsurgency.

- A Diplomatic Bridge Between ECOWAS and the AES — France no longer has leverage in Bamako, Ouagadougou, or Niamey, but it does have influence in Abuja, Accra, and the EU. Backing an ECOWAS recalibration, less punitive, more incentives, gives Paris a role that isn’t military and helps contain spillover to the Gulf of Guinea.

- Guardrails on Great-Power Competition — Don’t expect France to name Russia from the podium, but do expect language about “opaque contractors,” “disinformation,” and “accountability.” The goal is to nudge UN processes toward transparency requirements that constrain rivals without a direct confrontation.

Russia’s UNGA Message and Limits

Moscow will frame itself as the security partner willing to do what the West wouldn’t: deliver hardware, advisors, and political backing without lectures. The August defense summit with AES chiefs gives Russia a talking point and photo op. The catch is performance. If insurgent pressure keeps rising and blockades deepen, the “security without governance” model will be harder to sell, especially to coastal states wary of blowback.

Bottom Line

The Sahel is now a test of whether multilateral politics can still reduce real-world risk. France’s exit didn’t end the wars; Russia’s entrance hasn’t stabilized the front. What UNGA can do is force a package deal into view: humanitarian access, a political lane for ECOWAS-AES engagement, and basic guardrails for foreign military partners. That won’t stop JNIM or IS tomorrow. But it can slow the unravelling long enough for Sahel governments, and their outside patrons, to face the one truth this decade keeps repeating: without governance and economic relief, the firefight never ends; it just moves.

Dates to Take Note of —

UNGA 80 opened Sept. 9; the General Debate runs Sept. 23-29, 2025. Watch for side-event readouts from ECOWAS, AES representatives, and UNOWAS. The signals in those rooms, on access, timelines, and oversight, will tell us whether this UNGA mattered for the Sahel more than the last.

Ryan Parada is a Partner and the Chief Government Affairs Officer for Connector, Inc. where he oversees both domestic and international portfolios. He is a policy expert for our clients in numerous areas, including national security, energy, and the tobacco industry.